Attention Management: Information Overload

One side effect of learning how to learn is a voracious appetite for new information.

When I first learned the SuperLearner techniques I now teach and share with others, it rekindled my curiosity and helped me rediscover my early love of reading. With my newfound ability to consume information at superhuman speeds, I welcomed the fire-hose of content at the tip of my fingers. I read books and articles and listened to countless hours of podcasts indiscriminately. Why not? I reasoned that even if I didn’t have use for all of the information now, it may come in handy later! This is the mindset of a hoarder; keep everything “just in case.” And yet, as anyone who has filled their home with clutter in the name of preparation knows, no amount of stuff can bring peace of mind – in fact, it invites the opposite. Have you ever cleaned off your desk after months of random accumulation and just felt a weight lift off your shoulders? Clutter causes stress and invites distraction.

In the same way that clutter takes up space in the home and makes everything more difficult, information consumes attentional space, and too much of it at once can be disorienting. This quote from Herbert Simon sums it up beautifully:

“What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention, and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.”

―

Attention is a valuable resource. Don’t believe me? Advertisers spent ~$129 billion in 2019 in the US alone. Your attention is bought and sold for real money every minute of every day. It is valuable to advertisers for obvious reasons, but why is it valuable for you?

If you have spent any time in the self-improvement space, you have doubtless come across many techniques for improving time management skills. Time is a precious resource* and self-improvement gurus are right to treat it as such, but all the time in the world is worthless if you don’t have the capacity to make use of it! If you can’t effectively manage your attention, you can’t make use of your time. Time management is worthless without attention management.

Attention Management: External Factors

You have a limited supply of attention. To manage it, you first need to establish how much you have. Unlike time or money, attention lacks an established currency. You can’t keep track of it as easily as you might count hours or dollars, but that doesn’t mean it is impossible to measure or that it is entirely individualistic. For example, if you give a person the task of driving a car and texting at the same time (not advised), some people will do so with relative ease and some will drive through a hair salon almost immediately. However, if the task were to text while driving while reciting the national anthem while reading a book, everyone will fail every time; this is intuitive. This is related to what is known in the fields of Human Factors and Psychology as cognitive load and Multiple Resource Theory. The basic idea is that humans process different information in different ways and with different sensory pathways. A person can talk and drive at the same time because driving primarily requires kinesthetic and visual/spatial processing whereas talking and listening requires mostly auditory processing. These activities are complementary to some degree and represent a manageable cognitive load for the average person. Texting while driving is more difficult because the activities are less complementary as texting also requires visual and kinesthetic processing as well as an auditory component (subvocalization) and the second scenario is virtually impossible because it tacks on two more tasks that occupy the auditory and or visual space.

Before you can measure your attentional capacity, you need to decide on the factors to measure. There are a lot of different ways to cut the cake, but in this case, perhaps the easiest way is to differentiate by sensory pathways. Usually, when someone tells me that they are an “auditory” learner or something like that, what they actually mean is that they pay more attention to what comes in through their ears than through their eyes. Almost everyone (excepting those with severe aphantasia or the like) learns more effectively with visual information, but depending on genetics, upbringing, and lifestyle they may naturally pay more attention to information in a different format; I call this inclination attentional disposition. If you don’t intuitively know your attentional disposition, consider which of the following statements best apply to you:

- I cannot work in a busy atmosphere; if people around me are chattering, I’m useless.

- If there is a tv turned on in the room I will stare at it, no matter what is showing.

- I need to keep my hands occupied, otherwise I get distracted.

If you felt that number 1 applied to you most closely, you might have an auditory disposition. If you felt that number 2 was the best descriptor, you may have more of a visual disposition. If number 3 hit closest to home, you probably have a tactile/kinesthetic disposition. If you related strongly with two or all of them, congratulations! You are, like many others including myself, distracted by everything! And if you didn’t resonate with any of them strongly, then you are either very lucky, very uninterested in the world around you, or I didn’t write enough statements to adequately cover the spectrum.

Again, attentional disposition ≠ “type of learner,” don’t make the mistake of trying to convert all information into audio just because that is what you tend to pay attention to. Attentional disposition is a better indication of how you are most easily distracted than how you learn. If you are interested in learning more about attentional disposition, you can read more here.

Indiscriminately trying to consume as much information as possible for potential future use is like going to the store and blowing your entire paycheck to buy anything you see, but instead of spending money, you spend attention. Just as buying everything in the store would leave you broke with a house full of crap, careless expending of attention leaves you disoriented and swimming in useless facts and figures. What gets measured gets managed. This is the underlying principle of calendars, budgets, and diets. Any resource worth having is worth managing; any resource worth managing must be measured. This may be the reason attention gets overlooked – it is hard to measure. We have dollars, calories, hours, and… attention units? What is an attention unit? While there are different methods in the fields of human factors and psychology for measuring attention, they are mostly academic and impractical for the average person looking to get the most out of their day. The good news is, with some introspection and honest self-assessment, subjective reporting can go along way. Once you have identified your attentional disposition, you will know which types of stimuli you need to be extra careful to control, but there is more to attention management than just reducing distractions in your study space; you must also be considerate of internal stimuli.

Attention Management: Internal Factors

When I was a child, my imagination was out of control. I would get so consumed by the images flashing behind my eyes, that I became unaware of my surroundings and even my body. The excited energy would channel through my body and I would wave my hands around like a crazy person – true story. Thankfully, you can get away with some pretty socially unacceptable behavior as a child. Though they can usually mask it better, adults are just as vulnerable to such overload, but rather than exciting action scenes, this overwhelm is manifested in anxiety and unfiltered mental noise. This internal noise is so pervasive, that many people cannot even comprehend of not thinking. Internally dominant activities, such as studying and problem solving already consume a massive amount of attention without the turmoil; until you can achieve inner silence and escape from the noise, you will never be fully in control of your attention or your time. The most scientifically proven and anecdotally supported way to calm the storm in your mind is through some form of meditation. I am by no means an expert on the topic, but I have seen the benefits in my own life and highly recommend looking into the subject more deeply if you struggle to achieve mental silence.

“When we don’t have control over our thoughts, our brains constantly switch between a thousand different, mostly useless tasks. It’s thinking about how nervous you are for that big presentation coming up, how you are somehow always craving ice cream, whether or not you should have bought those shoes when they were on sale, whether there is any purpose to life, and, of course, that stupid song that has been stuck in your head for six hours. Simply put, most people are just too distracted to make well thought out decisions. The ability to focus on one thing, and consider it logically and carefully, is rare because it requires a mind free of overwhelming distraction. If you struggle with focusing on things that you really want to focus on, with letting your circumstances dictate your thoughts and emotions, with finding peace, I strongly encourage you to develop a practice of meditation. It doesn’t have to be an hour of sitting cross-legged listening to nature sounds every morning; it can be as simple as taking 5-minute breaks every once in a while, to just focus on your breathing, to relax, and to let your mind clear.”

-Out of Your Wheelhouse pgs. 97-98, Collin Jewett 2019

Managing the internal flow of attention-consuming information/stimuli is at least as important as managing the external. And while practices like meditation can help with reducing mental noise, there are ways to prevent it from growing loud in the first place. This is why it is important to have some prudence when stuffing one’s head. Learning begets more learning and enhances one’s ability to learn, but not all information is worth spending attention on. Consider establishing criteria for what you will let into your mind; I call this input filtering. These days, I try hard to avoid wasting attention on information that doesn’t inspire me or push me to be better. Rather than getting “overstuffed” with just-in-case facts and figures like I used to, I keep a library of links and references to potentially useful sources, and give my brain more space to breathe and be creative. Does it inspire you? Will it make you better? If not, what makes it worthy of your attention?

Attention Management: Attention Mapping

Schedules for time, budgets for money, diets for calories, and maps for attention. What is an attention map?

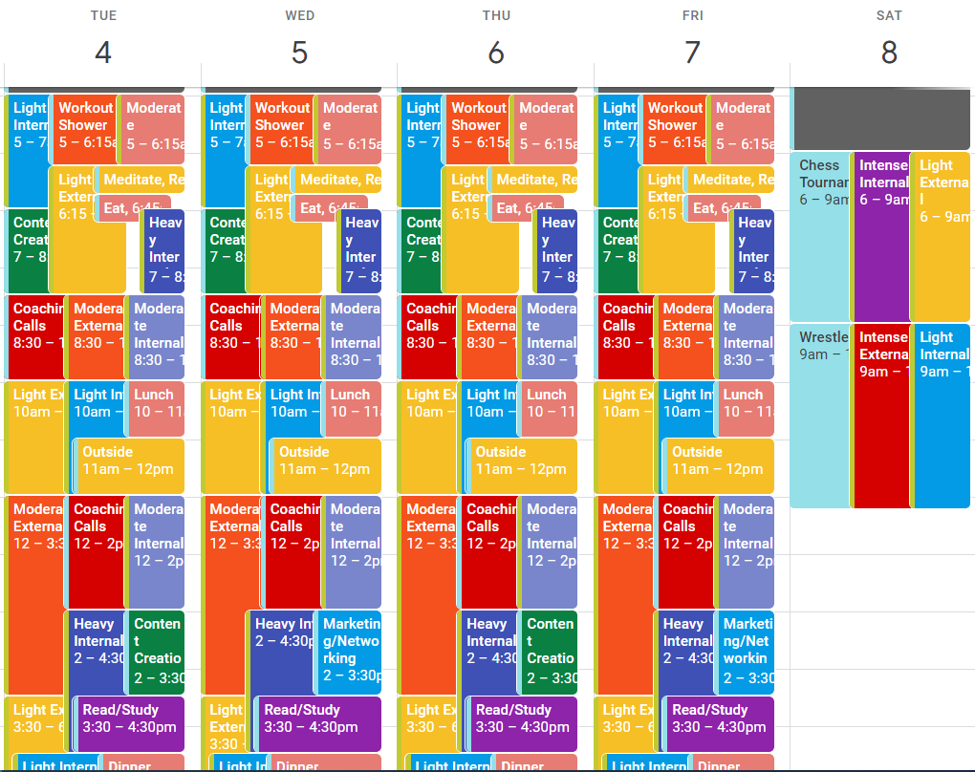

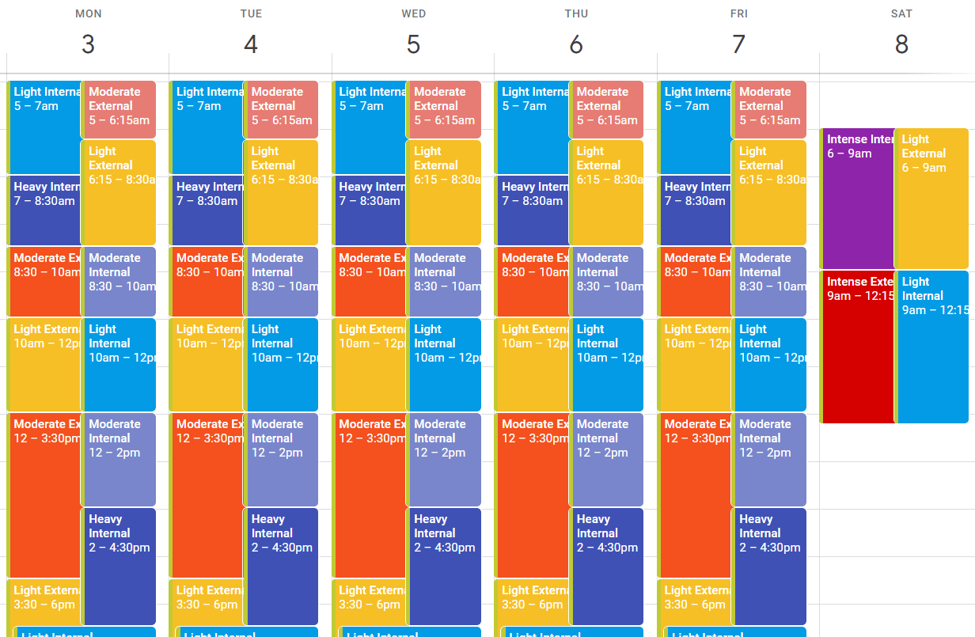

An attention map is a way of graphing and allocating attention over time, taking into account internal and external stimuli as well as total attentional capacity. Here is what and attention map looks like when overlaid on an example schedule:

Now, before you have a seizure just from looking at that, here’s what it looks like without the underlying schedule:

It is still a little busy, but once you understand what you are looking at, the important insights are easy to spot.

How to read and create an attention map

An attention map works in tandem with a calendar to create a visual representation of stimuli, and attention allocation, over a period of time. In the example provided above each day is the same (except for Saturday) – for simplicity – but unless your schedule is extremely consistent, yours will probably look less uniform. Colors are used to represent different levels of intensity, yellow(light)->red(intense) for external stimuli, and light blue(light)->purple(intense) for internal stimuli. The levels of intensity are subjective. For example, someone with a strong auditory attentional disposition might illustrate an orchestral performance with Lavender (Moderate Internal) and Red (Intense External), whereas someone with a visual attentional disposition might illustrate it with Light Blue (Light Internal) and Orange (Moderate External). It’s also important not to confuse the internal/external distinction with cerebral/physical; attention is always the domain of the mind. Working out, though highly physical, is often an internally dominated activity, either due to intense internal dialogue, or because it becomes routine and requires little spacial awareness to perform the motions, allowing the mind to focus on cognitive activities. The internal/external distinction is used to classify how your mental energy is spent, engaging with thoughts and feelings within, or with sensory experiences without. In general, the more experience one gains in an activity, the less externally dominant the activity becomes.

Once you have established what each color means for you based on your attentional disposition, it’s time to establish guidelines for each day and week. These guidelines can take many forms, but the most straightforward approach is to set time limits for different types of activities. When doing this, it is important to consider the fact that you have a limited amount of attention in any given moment. In the same way that you cannot take full advantage of nutrients or calories if you eat a week’s worth of food in one day, a week’s worth of attention must be spread out. The same is true on a smaller scale; you cannot spend a day’s worth of attention in one hour, or an hour’s in a minute. The brain can recover and refocus, but it takes time. You will notice that in the example above, the intensity of internal versus external stimuli is almost inversely proportional. This often happens naturally, but it is also worthwhile to create this pattern intentionally. It is hard to pay attention to several things at once! By varying the type and intensity of stimuli, you give your brain a chance to recover, and you are able to focus much more effectively. To test this, try for a moment to split your attention evenly between your senses. Focus 100% on external stimuli, ignoring internal thoughts and feelings and engaging completely with your surroundings, but do not treat any of your senses preferentially. You will quickly find this task to be impossible. Rather than experiencing sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures equally, you likely experienced a sort of rapid switching between the senses, focusing on the texture under your fingertips, then the appearance of your device, then the smell of the air. This is why multitasking is usually inefficient; it involves rapidly switching focus between multiple tasks rather than focusing on all at once. Successful multitasking is only possible when one or more of the tasks requires little to no focus because it is so routine – such as walking.

So, as you develop your own guidelines for managing your attention, I recommend trying to make your attention map look like a checkerboard. This approach will ensure that, at any given time, you are able to dedicate your attention primarily to a small number of inputs. Try to switch back and forth between internally and externally dominant activities and set limits for both each day. For example, if you find that you are easily overstimulated by external factors but can handle a heavier cognitive load, maybe set a limit of 3 hours of externally dominant activity per day and make sure that they are spread out to help you refresh mentally and physically. Remember that physical activity, such as going for a bike ride, isn’t necessarily externally dominant or intense; physical activities that are familiar can be a great way to let your mind rest, much like meditation. For the first week of attention mapping, it is okay to simply add colors to your pre-planned schedule. However, once you get the hang of it, make sure you establish a goal to strive towards and let that guide the process, otherwise, you will just be telling yourself something that you already know: your life is full of distractions. Use that first week to identify when you are feeling overwhelmed or unproductive and see if it was predictable based on the attention map. If the attention map looks more like stripes or monochrome than a checkerboard, you should expect to feel disoriented throughout the week.

Attention Management: In a Nut Shell

Attention is a limited resource, and should be managed as such. Information consumes attention. That information comes from without (externally) and within (internally). Activities that primarily involve engaging with the world around you via your senses are externally dominant; activities that primarily involve engaging with thoughts and feelings are internally dominant. How much attention is consumed by different types of information is largely dependent on one’s attentional disposition. To avoid unwanted attention consumption, external stimuli can be reduced through environmental control, while internal stimuli can be reduced through meditation and input filtering.

It is impossible to effectively focus on more than one thing at a time; successful multitasking is therefore only possible when one or more of the tasks requires virtually no attention to perform or the tasks are highly complementary. Just as money is managed with a budget, time with a schedule, and nutrition with a diet, attention can be managed with an attention map. Attention maps are a visual tool that works in tandem with a calendar and illustrate how different activities consume attention. By targeting certain color patterns such as a checkerboard, attention maps optimize one’s schedule for consistent focus.

Interested in learning more about how to maximize your time and your attention? I’ve got you covered.

*To call time a resource is somewhat of a misnomer. In reality it is a dimension with which resources can be measured.